Table of Contents

Gold’s value throughout history is deeply rooted in its distinctive physical and aesthetic attributes and scarcity. The allure of gold comes from its beautiful sheen and color, echoing the sun, an object of reverence across many cultures. Its malleability allows it to be crafted into various forms without losing its luster, as it does not rust, preserving its beauty and integrity over time. These characteristics make it not just a symbol of wealth but also of permanence and stability.

Why is Gold Valuable?

Gold is valuable because of its unique combination of physical properties—such as luster, malleability, and corrosion resistance—its scarcity and the extensive efforts required to extract it. Additionally, gold value is amplified by its profound historical and cultural significance across civilizations.

This blend of aesthetic appeal, practical utility, and embedded social and economic roles has made gold a universally sought-after commodity and a stable store of wealth for millennia.

The rarity of gold significantly enhances its value. Compared to common elements like copper and iron, gold’s presence in the Earth’s crust is minimal, found at just about .004 grams per ton. This natural scarcity means that gold is not easily obtained, adding to its value and often making it a symbol of prestige and power. Historically, this scarcity meant that gold was predominantly in the hands of the ruling elite, further cementing its status as a marker of wealth and influence.

Beyond its physical scarcity, gold’s value is also shaped by artificial scarcity. This is created through how gold has been hoarded, displayed, and used by those in power throughout history, reinforcing its association with status and wealth. In essence, gold’s enduring value lies in a unique combination of its inherent physical qualities and how societies have perceived and utilized it, often amplifying its scarcity and desirability through cultural practices and economic systems.

The relationship between gold and money is a complex interplay of economics, history, and social values. Historically, gold’s physical qualities and scarcity made it a prime candidate for use as money, a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value. The connection between gold and money, especially in the context of the development of capitalism and market economies, reveals much about the nature of economic systems and the concept of value itself.

- Physical Qualities and Natural Scarcity: Gold’s durability, malleability, and resistance to corrosion, combined with its scarcity, have positioned it as a preferred substance for use as money. These qualities make it easy to coin and durable as a medium of exchange, while its scarcity helps it retain value over time. These characteristics are practical and symbolic, reinforcing gold’s perceived value.

- The Work Behind Scarcity: Gold scarcity is not just a natural phenomenon but has also historically been produced and maintained through considerable effort. Mining for gold requires significant labor and resources; throughout history, controlling gold resources has often been a source of power and conflict. This work and struggle over control reflect the physical efforts to extract and produce gold and the social and economic systems that value scarcity as a means of increasing worth.

- Gold as Money and the Expansion of Trade: The transformation of gold into money facilitated the expansion of trade by providing a common medium of exchange that was universally valued. This universality allowed for generalizing market economies, where goods and services could be exchanged more freely across different regions and cultures. Gold-backed currencies provided a stable basis for international trade, contributing significantly to the rise of capitalist economies.

- Beyond Gold: The Evolution of Money: While gold played a crucial role in the early development of money and capitalism, its prominence has evolved. The shift towards non-commodity forms of money, such as paper currency and digital transactions, has not diminished the importance of understanding gold’s role in economic history. Instead, it highlights how the value of money—and gold itself—is shaped by social agreements, trust in institutions, and historical precedents.

- Historical and Social Value: Gold’s value as a money substance is deeply intertwined with its social value and historical significance. The esteem in which gold is held is not solely due to its physical properties but also its historical role as a symbol of wealth, power, and stability. This historical and social context is crucial for understanding why gold was readily adopted as money and how its value transcends mere physical scarcity or utility.

The history of gold production is marked by significant social and environmental violence, a fact that those involved in its extraction are often painfully aware of. This awareness suggests that the social value attributed to gold implicitly acknowledges these costs, even if it doesn’t deter its pursuit. Demonstrating that historical consumers of gold could have recognized and found significance in these impacts challenges the notion that concern for the consequences of gold mining was absent despite the apparent prioritization of its value and desirability.

Gold and The Philosophy of Money

The value of gold, particularly as it relates to money, is a nuanced topic that intertwines with its physical attributes and the complex web of social and political relationships it underpins. In “The Philosophy of Money,” Georg Simmel presents the idea that gold’s value as money partly derives from the sacrifices and efforts required to obtain it and the social structures it helps shape and maintain. Gold’s intrinsic value and scarcity initially made it an ideal substance for money, providing a tangible assurance of worth without established monetary systems. However, as societies evolved, the value of money based on gold shifted from its physical characteristics to its function in facilitating exchanges, acting as a store of value, and so on, rendering its commodity value increasingly irrelevant.

Simmel further explores the concept of sacrifice about the value of money, suggesting that using gold as money entails forgoing its use in other domains, such as jewelry. Yet, he acknowledges this sacrifice is not the primary source of gold’s value as money. More significant is the relinquishment of exclusive control over gold by royal, priestly, or aristocratic classes, democratizing its value and integrating it into more comprehensive economic systems. This transition reflects a broader societal shift, where the value of gold as money and its role in economic transactions underscore the interplay between economic utility and social power dynamics, illustrating how contests for social power are mediated through economic instruments like gold.

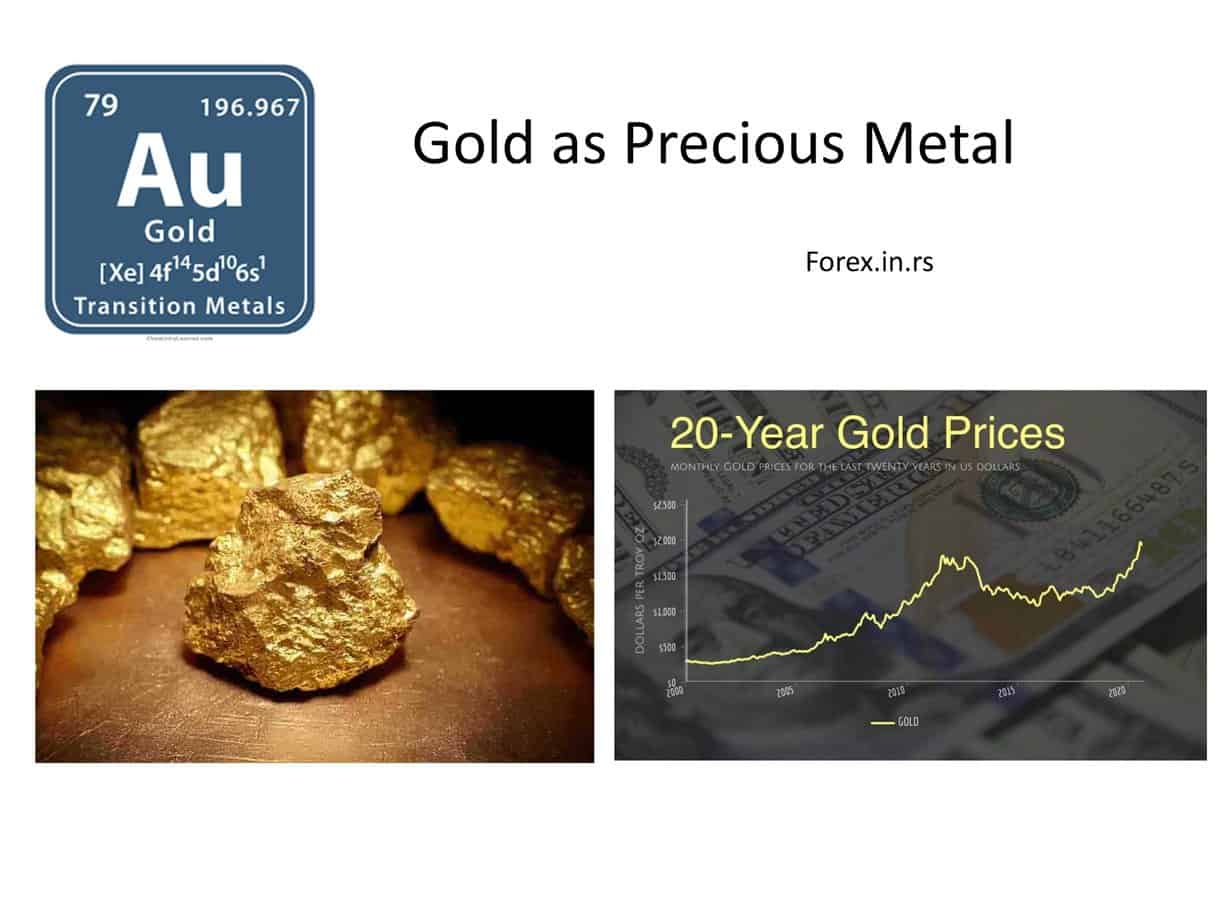

Gold Standard and Value of Gold in Modern Times

In modern times, the value of gold and its role in the gold standard highlight a complex interplay between economic growth, technological advances, and monetary policy. The discovery of significant gold deposits in the 19th century, particularly in the US and Australia, and later in South Africa, massively increased gold production and introduced large amounts of gold into global circulation, initially boosting the use of gold coinage. This proliferation of gold helped establish the gold standard, a monetary system where currency value is directly linked to gold, facilitating international trade and economic stability by ensuring currency could be exchanged for a fixed amount of gold.

The gold standard required a balance between the gold held in reserve and the amount in circulation. Central banks needed to hold only a fraction of their currency’s total value in gold, allowing the rest to circulate as paper money or in other forms. This system hinged on the trust that paper money could be converted into gold despite the central banks holding a minimal amount of actual gold in reserve compared to the total money supply. Over time, however, the emphasis shifted from physical gold to the functions of money as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value, leading to the eventual abandonment of the gold standard in favor of fiat currency systems, where the value of money is not based on physical commodities but rather on trust in the issuing authority.

The shift from the gold standard reflects broader economic and social changes, including increased faith in state institutions and the move towards more flexible monetary systems that can better respond to economic challenges. Despite the end of the gold standard, gold continues to hold substantial value as a physical commodity and a financial asset, illustrating its enduring legacy in shaping economic systems and practices.

Gold is Not Valuable Only Because of Rarity!

While the value of gold is significantly influenced by its rarity, scarcity alone does not determine its value. This becomes apparent when comparing gold to other precious metals, some of which are rarer yet may not command a similar market value or historical significance. The valuation of precious metals is a complex interplay of factors beyond mere rarity, including industrial utility, cultural significance, market demand, and historical context.

- Platinum and Palladium: Both metals are rarer than gold in the Earth’s crust. Platinum, for instance, is highly valued for its use in automotive catalytic converters, jewelry, and investment. Palladium, similarly, has seen increasing demand in automotive applications for gasoline engines and electronics. Despite their scarcity and utility, gold’s historical and cultural prestige often surpasses platinum and palladium. For much of history, gold has been a cornerstone of monetary systems and a symbol of wealth and power, contributing to its high valuation.

- Rhodium: Rhodium is another metal significantly rarer than gold and has seen periods where its price per ounce far exceeds that of gold. Its primary use is in automotive catalytic converters, which have increased in value due to demand. However, the rhodium market is much smaller and more volatile than gold’s, lacking the same historical and cultural significance level. This lack of a broad demand base outside industrial uses makes its value more susceptible to sharp fluctuations.

- Silver: While more abundant than gold, silver has a unique value proposition due to its industrial applications and historical use as money. The industrial demand for silver in electronics, solar panels, and other technologies contributes to its value, but it does not rival gold in terms of investment and monetary use. This illustrates that scarcity is not the sole driver of value; utility, historical context, and the breadth of demand across different sectors also play crucial roles.

Facts and Figures:

- Abundance: Platinum is approximately 30 times rarer in the Earth’s crust than gold. Palladium and rhodium are also significantly rarer than gold.

- Industrial Use: About 40% of platinum and palladium demand comes from automotive catalytic converters. In contrast, a significant portion of gold’s demand comes from jewelry (around 50%, according to some estimates) and investment (around 40%), with a smaller portion for industrial uses.

- Historical and Cultural Significance: Gold has been used as a form of currency, wealth storage, and jewelry for thousands of years across various cultures, enhancing its desirability and perceived value.

Therefore, gold’s value is a multifaceted phenomenon that cannot be reduced to rarity alone. Its enduring status as a store of value, a hedge against economic instability, and a symbol of wealth and prestige, combined with its physical properties and market demand, contribute to its high valuation compared to other precious metals, even rarer ones.

Conclusion

Gold’s value transcends its physical rarity and is deeply rooted in historical significance, cultural symbolism, and economic functionality. It is a precious metal and a cornerstone of financial systems, reflecting trust and stability across ages and civilizations. The interplay of its aesthetic appeal, industrial utility, and investment desirability ensures its continued prominence in global markets. Ultimately, gold’s enduring value is a testament to its unique position at the crossroads of beauty, utility, and human tradition.

Investing in IRA precious metals can protect your retirement fund. Investors with Gold IRAs can hold physical metals such as bullion or coins. Get a free PDF about Gold IRA.

GET GOLD IRA GUIDE